Spencer Theater for the Performing Arts, Alto, New Mexico 1997 |

SUN Lingbo Interview with

Antoine Predock for World Architecture 2008/10

1. First, I would like to thank you for this interview

of WA.

As we know, you are a productive architect since you started your own

practice in 1967, you’ve won many competitions and awards, including

the AIA Gold Medal, you started at New Mexico, and now having an international

reputation.

I would like to start from the very beginning of your academic and professional

career. I know that you were an engineering and architecture student at

University of Mexico, and then you went to Columbia to study architecture,

you also went to Taliesin and met Wright during that time, how these early

education and experience affected your attitude to architecture?

You came up when Modern Movement was quite big in the States, as an architectural

student in 1950s, do you think Modernism is still fundamental to your

background? Were there any special masters, movements that left a deep

impression?

My early education was grounded in modernism and

my work generally drifts toward minimal expression but the influence of

Louis Kahn when I was a student profoundly affected me. Through his theories

and work I understood there were critical areas of subjectivity that could

enrich a solely modernist approach. Wright’s intensity with regard

to detail was also very important to me.

2. Most of your early works were in New Mexico. You wrote

in your book:” New Mexico has formed my experience in an all pervasive

sense. I don’t think of New Mexico as a region. I think of it as

a force that has entered my system, a force that is composed of many things.”

Could you please say something about the force you mentioned?

By working in New Mexico, and responding to the particular landscape and

culture, you were kind of distant from those stylistic movements. Do you

think that’s the reason why your works are distinct comparing with

those in East or West Coast of America?

As for young architectural students today, there seems to have so many

disciplines and theoretical models in the world, which make them confused

and hard to choose which way to follow. What are your comments on that?

How do you feel about the various stylistic movements?

The force of New Mexico is a summation of geologic

time and power, and cultural strata going back thousands of years all

combined with an astonishing natural beauty. In my early work and at present,

although now I only work infrequently in New Mexico, its climatic and

environmental specificity makes the result different from US East or West

coast movements. For students, working in a confusing and sometimes contradictory

theoretical milieu, the important thing to remember is that there are

good and bad aspects of globalization. The worst examples in architecture

are buildings that are merely transplanted from other cultures and locations.

Architecture should grow from its site, responding to the site’s

physicality, layers of occupation, technology and spirit. Each building

should be a singular unique event of its time and place.

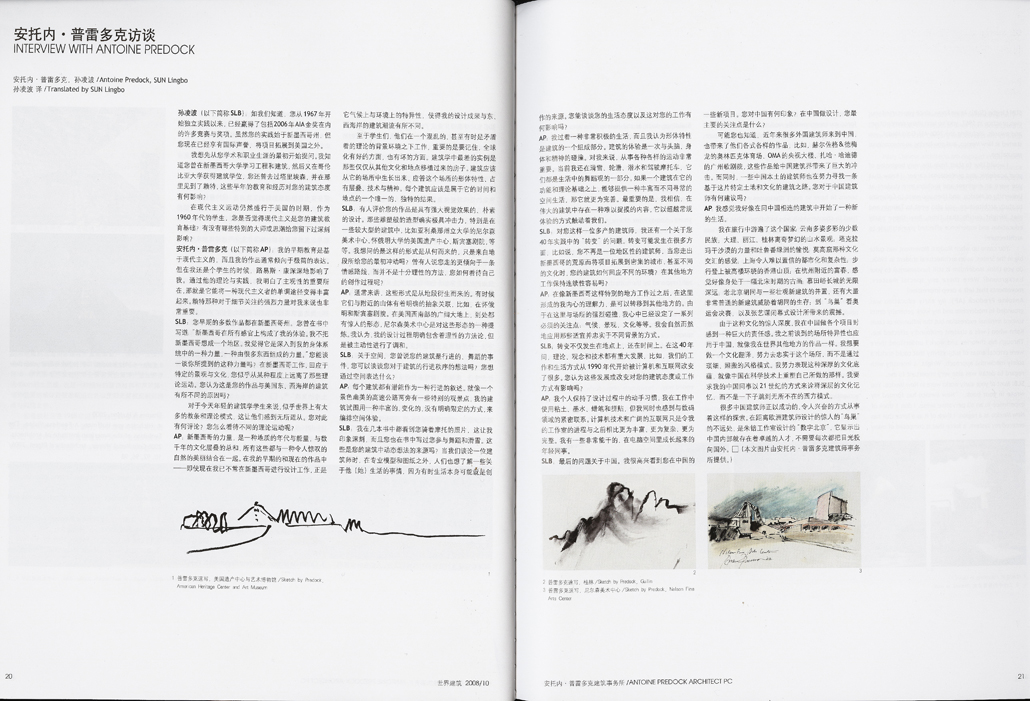

3. Someone said your work were austere designs of enormous

visual impact. Those sculpture shape, simple and evocative forms are really

impressive, and always beyond expectation, especially in the large-scale

buildings, such as the Nelson Fine Arts Center at Arizona State University,

the American Heritage Center at University of Wyoming, and the Spencer

Theater, etc.

I was wondering what determine those forms? Do they just come from the

initial impulse at the site? And there are sketches and clay models in

your portfolios, are they starting points of the forms?

People said you took an emotional route rather than a rational methodology,

what do you think of your process of making?

These forms are derived from site in a general sense.

Sometimes there are specific abstract relationships to nearby mountains,

as in Wyoming and the Spencer Theater. In the US Southwest, amazing forms

on the horizon are everywhere and the Fine Arts Center makes a kind of

distillation. I think my design process definitely embodies rational methodologies

but tempered by the initiative.

4. On space. You once said that your buildings are processional,

choreographic events, could you say more about your thought on the processional

ordering of your building? What do you want to express through space?

Every building has the potential for processional

narrative. Much like a scenic highway with special vantage points along

it, my buildings attempt to orchestrate spatial experience in a rich,

varied, open-ended way.

5. In several books, I saw photos of you riding a motorbike. It is quite impressive. And you also wrote about your involvement in dance and ski in your book. Are they the sources of the notion of motion in space of your buildings? When we talk about an architect, besides the professional models and drawings, people also want to know something about his/her life, because sometimes the life itself could be the source of creation. Could you talk something about your approach to life and its influence on your work?

I lead a very active life and I think physicality is a part of architecture.

The experience of architecture is an encounter with mind, body and spirit.

It is important for me to be involved in various kinds of motion. Currently

– skiing, inline skating, scuba diving and motorcycles. Those are

all part of the choreographic aspect of life. If a building provides a

rich and surprising spatial life beyond its functional and theoretical

underpinnings then it is more complete. Above all, I believe there is

an intangible content in great architecture that touches us in ways that

transcend routine experience.

6. For a productive architect like you, I also have a question about “transition”

in your 40 years of practice. Transition could take place in many aspects.

For example, since you are no longer a regional architect, when you go

out of the desert landscape of New Mexico and expand your projects to

the dense cities, even to different cultures, how your architecture would

respond to that different situation? Is it easy to have continuity when

works elsewhere?

Understandings that have grown within me working in an extraordinary place

like New Mexico are translatable to other locations. Because of the intensity

of the encounter with place here, I have a kind of inventory of considerations;

climate, landscape, culture, etc, that I automatically apply in ways that

are appropriate and true to different contexts.

7. The transition is not only in location, but also through times. During

these 40 years, there are great developments in theories, ideas, and techniques,

for example, our working and life style changed a lot by computer and

internet since 1990s. Do you think those developments or changes have

affected your attitude to architecture or your way of working?

I personally retain a hands-on connection to my design

process working with clay, ink, pastel and collage, but I feel deeply

connected to the digital realm at the same time. Computer technologies

and the expansive internet only make my studio’s process richer,

more complex and more complete than ever before. I have extraordinarily

talented, young colleagues who have grown up in cyberspace.

8. The last question is on China. I am glad to see some

of your new projects in China. What is your impression on China? When

you design in China, what are your primary concerns?

As you might know, many foreign architects came to China and bring their

fancy works in recent years, like the Olympic Stadium by Herzog &

de Meuron, CCTV Tower by OMA, Grangzhou Opera House by Zaha Hadid, which

have great impact on China’s architectural community. While at the

same time, some local Chinese architects are trying to find a way for

architecture based on this particular land and culture. What suggestions

would you like to give to Chinese architects?

I feel as though I am beginning a new life in architecture

connected to China. My travels have taken me throughout the country; the

fantastic ethnicity of Yunnan; Dali, and Lijiang, the surreal landscapes

of Guilin, the power of the Taklamakan Desert and the delight of the Turfan

oasis, a sense of cultural crossroads at the Mogao caves, Shanghai’s

incredible urbanism and sophistication, hiking to the peak in Hong Kong

surrounded by its high rise dance, the feeling of being part of a Northern

Song Dynasty painting at Fuchun near Hangzhou, the infinity of the Great

Wall at Mu Tian Yu, Hutong of Beijing juxtaposed to some sensational new

buildings and many very average new buildings that threaten the Hutong’s

existence, attending the Olympics finals in the Bird’s Nest and

the thrill of Zhang Yimou’s design for the closing ceremony. Because

of the astonishing depth of this culture, I feel a great responsibility

working on various projects in China. The site specificity that I have

spoken of before applies in China just as in other works of mine around

the world. I feel like a cultural translator trying to be true to the

place but not in a trivializing, literal stylistic way. I try to engage

the vast cultural depth as China reinvents itself technologically. I urge

my Chinese colleagues to draw from deep cultural memories in a 21st Century

fashion and not to jump to the omnipresent Western models. Many Chinese

architects are engaged in this search in successful and provocative ways.

A short distance from the fabulous Bird’s Nest designed by European

architects is The Digital Building by Studio Pei-Zhu which shows that

great talent exists within China without the need to look outside the

country every time.